Investors interested in the stock market and financial news follow the Federal Reserve Bank, the Fed, as closely as Fox Mulder followed the cigarette-smoking man, but if you don’t care about stocks and bonds, you may wonder whether you should care about a big, boring bank.

You most definitely should care. The Fed is among the most important institutions in our country, yet news coverage about its operations and decisions is scarce and misleading. Nevertheless, the truth is out there, and just as the cigarette-smoking man seemed like a bore, what he was up to was not.

My reference to the cigarette-smoking man is apt because the Fed has a conspiratorial origin. Even the title of left-wing William Greider’s book, Secrets of the Temple, suggests a conspiracy, as does right-wing Gary Allen’s None Dare Call It Conspiracy. Other books about the Fed’s history are New Left historian Gabriel Kolko’s Triumph of Conservatism, which has a chapter on the history of the Fed, and libertarian economist Murray Rothbard’s What Has Government Done to Our Money and Mystery of Banking.

The conspiracy, easily verified in these sources and on the Fed’s website, is that in 1910 three bankers secretly conspired with Senator Nelson Aldrich (grandfather of late Vice President Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller) on Jekyll Island, North Carolina, to establish the Fed. The bankers represented three banking empires: that of JP Morgan (Henry Davison), Kuhn Loeb (Paul Warburg), and John D. Rockefeller Sr. (Frank Vanderlip). Also present were a professor, A. Piatt Andrew, and Senator Aldrich’s personal secretary.

The group laid out a plan for a central bank that a Democratic Congress passed into law in modified form four years later. Woodrow Wilson signed the bill two days before Christmas in 1913. Just like today, coverage in the New York Times was misleading so that few Americans understood the Federal Reserve Act’s implications.

The Fed inspires love among Democrats, big-government Republicans, and establishment conservatives, but disdain among small-government Republicans and classical liberals like Ludwig von Mises. President Trump has been critical of current Fed chairman Jerome Powell, but meaningful reform of the Fed will be an uphill battle because it is powerful.

The Fed is tightly linked to America’s commercial banks and Wall Street. One way to look at the Fed is that it is a government-mandated, anticompetitive agreement or cartel among American larger commercial banks. Its current chairman, Jerome Powell, was a partner of the Carlyle Group, which has $425 billion under management. Federal government operations and the current structure of the world economy currently depend on it, although that may change in coming decades.

Writing in 1912, Ludwig von Mises said, in his Theory of Money and Credit, that money is just like any other commodity and that there is no need for a central bank. Von Mises predicted that a pure paper-money system run by a central bank like the Fed, which was established in 1913, would lead to escalating income inequality, and that turned out to be true.

Subsequently, Milton Friedman proposed that the Fed be restrained by a fixed money-creation rule. Friedman’s idea was that the Fed should be bound by law to increase the money supply at a fixed, say two percent, rate each year so that there would be no need to back the dollar with gold. President Nixon abolished the final leg of the gold standard in 1971, and Friedman’s idea did not work when Fed chair Paul Volcker tried it in the early 1980s, so the Fed is free to expand and contract the money supply, the number of dollars in circulation, at will.

You may have thought that there is something like gold or silver that backs the dollar and other major currencies, but there isn’t. The dollar is backed only by the full faith and credit of the United States. Increasingly, though, the federal government hasn’t acted in good faith and hasn’t been deserving of credit, so the Fed’s global system is increasingly unstable. About half the dollars the Fed has printed are overseas in the form of petrodollars (Saudi Arabia) and Eurodollars (China and Europe). If the system falters and those dollars return to the US, there may be hyperinflation here.

The number of dollars in circulation affects you in three ways: First, if the Fed prints more money than productivity increases, price inflation follows. That happened during COVID.

Second, when the Fed prints more money, interest rates, the price of money, go down. Just as the price of cars goes down if carmakers produce too many cars, so does the price of money, interest rates, go down if the Fed prints too much money. The Fed doesn’t really print the money; the money is electronically deposited, but the image of printing has been with us since the days of Benjamin Franklin, who favored a paper money system because he thought he would get the printing contract.

Money printing stimulates new businesses, real estate development, house purchases, car purchases, and other economic activity because lower interest rates mean it’s easier to pay back loans. The reverse happens if the Fed takes money out of circulation. That has been happening since late 2021 because of inflation.

Increased economic activity benefits many people. The people it benefits the most are the institutions who get the fresh money earliest because as the money circulates, it causes inflation. People who get it later, such as workers, get less buying power per dollar. The institutions that get it first are Wall Street, large corporations, and the federal government. The people who never get the fresh money are those who are poorest and can’t borrow. Middle class Americans see the money after Wall Street, the US government, and large corporations get the first dibs. The middle class gets a benefit from inflation’s reducing the real value of their mortgages, but they are harmed because inflation suppresses wages.

Third, when the Fed prints more money, real estate, stock, and bond prices go up, and when the Fed reduces the amount of money, the stock and real estate markets fall. By changing the rate at which it increases the supply of money, the Fed decides when recessions occur, how much inflation there will be, and how high the stock market will go.

Although the president appoints the Fed’s chairman and its Board of Governors, the member banks own shares of the Fed’s stock and receive dividends. The list of member banks is long (it is available if you google “Mitchell Langbert Blog list of member banks” and includes all national banks and many state-chartered banks. All American banks participate in the money-creation process. The Fed prints reserves, and the banking system expands them tenfold.

The process works like this: When the Fed wants to expand the money supply, it prints new money out of thin air to purchase treasury bonds, usually from a large, money center bank like Citigroup or Bank of America. The large bank then lends the new money to an institutional client, such as Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, or Johnson and Johnson.

The large client deposits the funds before using them for investment. They deposit their funds, possibly in another bank, which then can use 10% of the deposit as reserves and lend the rest to another borrower. If Goldman Sachs deposits a loan from JP Morgan in Citibank, Citibank can then lend 90% of the deposit to a second corporation, say Nvidia. Nvidia deposits the 90% in Wells Fargo Bank, which can then lend 81% (90% of 90%) to a third corporation.

When the process is complete, the money supply has increased by 10 times the amount of money originally printed. When loans are paid off, the money supply is reduced, and the Fed needs to create new money to keep the money supply stable. The biggest, most creditworthy clients get first dibs. The little guy is further down the food chain.

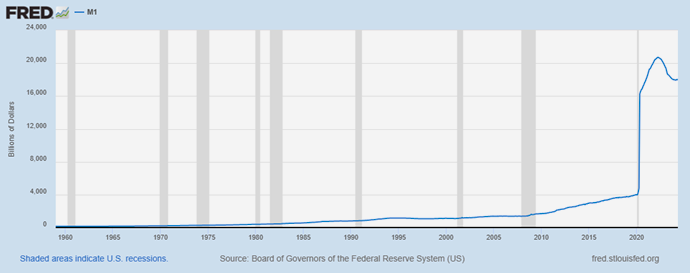

There are several measures of the money supply, but the simplest one is M1, cash, checking accounts, and NOW accounts. The St. Louis Fed tracks the historical growth of M1, copied below. The spike in 2020 was because of President Trump’s COVID measures. It masks earlier spikes that were large at the time, especially during the Bush-Obama 2008-9 bailouts.

Who benefits most from the banking system’s relentless expansion of the money supply? Since 1971 real hourly wages have barely budged. That’s because of the inability of workers to predict inflation rates. Workers continually play catch-up. Prior to 1971, the year the last remnant of the gold standard ended, wage increases tracked productivity, as economics predicts they should. Inflation-adjusted wages grew at a .5% to 1.5% annual rate in the 19th century and more in the 20th. That wages have not followed economic logic and have failed to track productivity growth since 1971 is evidence of government intervention, specifically, the Fed’s monetary expansion. Keynes and von Mises, who come from opposite ends of the spectrum, both predicted that this would happen due to what Keynes called money illusion: Inflation blindsides workers.

It does not do the same to investors. The large corporate borrowers who receive money earliest in the money-creation cycle get a counterfeiting benefit. Wall Street benefits as well because lower interest rates resulting from monetary expansion boost the stock market, which creates bubbles and manias.

Falling interest rates increase the value investors place on future earnings. If the interest rate is 10% today, today’s valuation of a $1 dividend receivable in one year is discounted for the 10% interest an investor could have received by saving in a bank, so a dividend dollar received in a year is worth 91 cents (1/1.1 x $1) today. If the interest rate falls to 1%, the dividend dollar next year is worth 99 cents (1/1.01 x $1) today because an investor could have alternatively put 99 cents in the bank and gotten a dollar in a year. The increase from 91 cents to 99 cents suggests how returns from dynamic firms that will produce increasing incomes over many years can be juiced by reducing interest rates. That is why tech firms have done so well: Their success is linked to the Fed.

The three banking empires that conceptualized the Fed, those of Rockefeller, Kuhn Loeb, and Morgan, knew exactly what they were doing. The history goes back further, of course, to Alexander Hamilton, economist Henry Charles Carey, Henry Clay, and Abraham Lincoln, who was a railroad lawyer and real estate investor. The opponents of central banking were the Antifederalists, Jefferson’s Democratic Republicans, and Andrew Jackson. As Arthur Schlesinger describes in The Age of Jackson, in the 1830s workers understood that paper money was not in their interest. Today, I am continually surprised that those who are most adversely affected by the Fed continue to support it.

Mitchell Langbert is a former Associate Professor of Business at Brooklyn College