A cause to end the genocide in Pakistan

By Robert Golomb

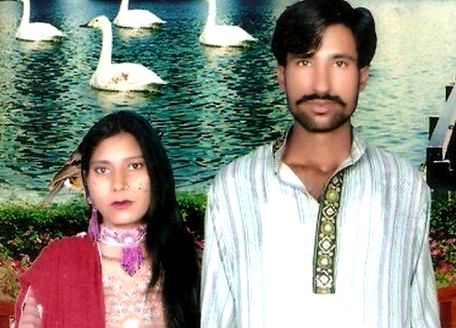

Sajjad Maseeh and his wife Shama Bibi were burned alive

by mobs of Muslims

It was on one of the first days of November 2014 that the rumor spread throughout the city of Kasur in the province of Punjab in the nation of Pakistan that Sajjad Maseeh and his wife Shama Bibi, both Christians, had burned verses from the Muslim holy book, the Koran. The formulation of that rumor was soon followed by the formulation of a mob of some 1,200 outraged Muslims who trailed Sajjad and his wife to the industrial building in which they both worked.

Because the leaders of the mob wanted to prevent Sajjad and Shama from fleeing, they broke their legs. (Shama was the mother of their four young children and was four months pregnant at the time.) And because Shama was wearing an outfit that didn’t easily burn, she was wrapped in flammable cotton. The mob then held the couple over a brick furnace until their clothes caught fire, before throwing both of them into that same brick furnace in which they were both burned alive.

This atrocity was witnessed by scores of onlookers; among them was Javed Maseeh, Sajjad’s first cousin. Javad, who had pleaded in vain to the mob to spare the couple, spoke these chilling words over the telephone to America’s NBC News several days after the attack: “The bones are still being found. Friends keep collecting them and bringing them to us in batches of twos and threes. We will bury these bones when we have [enough} for the bodies. But we will not find all of them. I’m sure.”

Muslims burned Christian homes and churches in Pakistan

In Pakistan, tragically, similar and other acts of barbarity have become commonplace against Christians, who represent approximately four percent of that South Central Asian nation’s estimated 200 million population — of which the majority is Sunni and between 12 and 20 percent are Shi’a Muslims — and also against all other religious minorities including Hindus, Sufis and the Ahmadiyya (a technically Muslim sect), who combined make-up about one percent.

In fact, so commonplace in that nation — both before and after the murders of Sajjad and Shama — are these religiously motivated crimes that even when the western media report them, such news seems to be almost immediately forgotten by the general public and their respective leaders throughout the western world.

So there was little international outcry when, in April 2006, 30 Hindus were murdered by Muslim terrorists in the Pakistan city of Duda. And there was little international public outcry when, in May 2010, Sunni mobs launched simultaneous attacks against two Ahmadiyya mosques, killing 94 and injuring more than 120 innocent members of that Muslim minority sect in the province of Lahore. That deafening sound of silence continued when, six months later, in the same city of Lahore, 50 followers of the Sufi religion were murdered and more than 200 were injured when suicide bombers detonated bombs in their holy shrine.

Nor were there discernible voices of outrage when, on September 23, 2013, a suicide bomber attack killed 126 and injured more than 250 Pakistani Christians who were attending church services in the city of Peshawar, and the unspeakable silence still remained when, on March 15, 2015, 15 more Pakistani Christians were slaughtered and more than 70 others wounded by terrorists who detonated their bombs while the victims were engaged in their religion of peace, once again in the tragic province of Lahore.

All of these once-living human beings — girls, boys, women, men who once lived on our earth — have been reduced to just a number among the toll of the dead. One of the most significant political events leading to these atrocities occurred in 1973, although it seemed to be benign at the time.

In that year, then-President Zulficar Ali Bhutto persuaded the National Assembly (Pakistan’s national legislative body) to adopt a new constitution establishing a parliamentary system of government. The new constitution, the fourth since Pakistan secured its independence in 1947, appeared at the time to be a great gift to all of Pakistan’s religious minorities.

The three prior constitutions, which were constructed with provisions limiting the rights and freedoms of minorities, went against the core principles of Pakistan’s Sunni founding father Ali Jinnah, who championed the idea that citizens of all religions should be treated equally.

Of the three constitutions, from a historical prism, many in the region today believe that it was the first constitution, which changed the name of the nation from the Democratic Nation of Pakistan to the Islamic Nation of Pakistan, which struck the initial legal and symbolic blow against the rights of minorities, leading to the genocide that was to follow.

With the passing in 1973 of the then new fourth constitution, which introduced a democratic form of parliamentary governance in which all citizens could cast their vote, Jinnan’s earlier concept of a Pakistan that treated all of its citizens humanely, fairly and equally seemed at first glance to becoming a reality. But it didn’t turn out that way.

While the fourth constitution expanded the rights of all citizens to vote in parliamentary elections, it contained amendments that, rather than expanding as first hoped, severely restricted the civil rights of minorities. Under the provisions of the fourth constitution, the Muslim Holy Book, the Koran, became the “supreme law” of the nation, which, ominously, under the new constitution, separated its citizens into two separate categories — “Muslim” and “non-Muslim”.

The climate had been set for worse to come in the following decade. Between 1980 and 1986, the military government of General Zia ul Haq perfidiously expanded the Blasphemy Laws, making the alleged desecration of the Koran a crime punishable by life imprisonment and making the alleged blasphemy against the Prophet Muhammad a crime punishable by life in prison or death.

These abominable new provisions were a perversion of the law’s original intent. Begun benignly in 1860 by Pakistan’s then-British rulers, the law’s original purpose was essentially to safeguard the religious rights of Muslims. But after Pakistan’s independence in 1947, the Blasphemy Laws incrementally disintegrated from protecting the rights of Muslims to denying the rights of all non-Muslims.

That hateful climate created first by the fourth and three preceding constitutions and then by Zia-ul Haq’s application of the Blasphemy Laws, adhered to by Pakistan’s current ruler, Nawaz Sharif, is what has directly led to the atrocities perpetrated by gangs of angry Muslim mobs like those in Islamabad, Kasur and Lahore and in countless other cities, towns and provinces throughout Pakistan for the past 35 years, according to most journalists and scholars who follow the region today.

Portests against the burning of the Christian couple and blaspehmey laws

Concurring fully with that view is a very special man named Pervez Rafique, a Pakistani political refugee, who came to my Long Island office from his temporary residence in Queens, New York, to talk about the painful past and tragic present of his native country. “The genocide that is taking place in Pakistan today has very dark roots, beginning with changing the name and basic idea of Pakistan from a democracy to an Islamic state, to labeling its citizens as Muslim or non-Muslim, and then finally these past awful thirty-five years to these barbaric Blasphemy Laws.” The founder in 2014 of Bleeding for Belief, an American-based organization formed to attempt to put an end to the genocide in Pakistan, Rafique, 45, possesses a deep personal understanding of the evil these laws have spawned.

In January 2011, his close friend and political ally Salman Taseer, the former Muslim governor of Punjab, was assassinated by religious extremists. His murderers’ grievance:Taseer was a leading and highly respected voice opposing the Blasphemy laws. In March of that same year, another close friend and ally of Rafique, Shahbaz Bhatti, the Christian former federal minister

for minorities, was assassinated by religious extremists, for the same reason that Taseer had been murdered two month earlier.“It was a very sad and tragic time for me and for all peace-loving people of Pakistan. I had lost two friends, and the people had lost two strong voices for human rights for all people of Pakistan,” he said.

Serving at the time in the Punjab parliament in one of the few seats that minorities were permitted to hold, Rafique, despite numerous death threats, continued the crusade that had been begun by his two fallen friends. However, when in the beginning days of 2014, he received information from his political allies that religious extremists were planning his imminent assassination, he fled to America as a political refugee.

Now married and the father of a one-year-old daughter, Rafique spends most of his waking hours working through Bleeding for Belief to end the genocide in Pakistan. That work includes frequent trips to Washington’s Capital Hill, where he often meets with members of Congress. “I have, in my capacity as president of Bleeding for Belief, had regular meetings with members of Congress and their staffs to try to get their help to stop this carnage. At our urging, Congress has passed resolutions calling for the government of Pakistan to fight the militants who are committing these crimes. It is my hope that while pressure coming from Congress has not worked yet, as it continues, the Pakistani government will finally agree to follow their demands.”

Rafique has also through his foundation met with both secular and nonsecular leaders in the American Christian, Hindu, Muslim and Jewish communities. He said that he has been encouraged by their words of support. “A minister explained that as a Christian he could forgive the terrorists but would do every thing in his power to defeat them,” Rafique said. “A Hindu Priest told me that while his religion forbids speaking badly of even the wicked, it was the duty of all Hindus to overcome the forces of evil, in Pakistan and throughout the world. Both a Muslim cleric and a secular leader of the Muslim community together expressed their horror over the killings, and explained that the Muslim religion preaches peace, and that the genocide of people practicing different faiths is the sole work of religious extremists who for now have hijacked their religion. These and all the other leaders I met promised their total and unconditional support to help end the genocide.”

Rafique added that he was particularly touched by the kind and sympathetic words of men and women of the Jewish religion: “To my Jewish brothers and sisters, this modern genocide brings back horrible reminders of the Holocaust committed against the Jewish people. One even told me that she hears the cries of her own murdered brethren as she learned about what is going on in Pakistan and throughout the Middle East today.

“What I share with all of these Jewish people” Rafique elaborated, “is the belief that if the leaders of Muslim nations followed the policies of Israel, which grants all rights and privileges to all non-Jews, the problems we face today would be over. And it is my hope,”Rajad added “that one day every Pakistani Christian, who the present government forbids from visiting the holy land, will be free to visit the nation which gave birth to Christianity.”

Rafique then talked about the genocide of Christians, in particular, throughout the Middle East. “The genocide against Christians in Pakistan is, as we are speaking at this very moment, also taking place against Christians in Iran, Iraq, Syria, Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf states,” he stated. “What is stopping the good and kind nations of the world from using their influence and power to putting an end to the suffering of all victims of religious hatred in all places in the world?’ Two of these victims were named Sajjad Maseeh and Shama Bibi.

Robert Golomb is a nationally and internationally published columnist.